Before moving to New York City, I worked for a large law firm in Canada. Like most national Canadian firms, we had a Montreal office. As you will know, language is politicized in Quebec, even more so than in France itself. The French Language Charter, or Bill 101, requires that French take precedence over any other language in Quebec commercial signage. The law has been administered with such fervor as to give rise to ludicrous situations, like #pastagate, an incident in which a restaurant came under scrutiny for its use of such “exotic” words as pasta, or a requirement that another local restaurant rename its signature dish – fish and chips - “poisson frit, et frites”. What you may not know is that these strict language laws apply similarly to resources used in commercial contexts. Implementation must occur in French if the resource is available in French. If a tool can be implemented in French and English, that’s fine, but the French version is required. Best efforts must be exercised to implement tools and technology bilingually, which means that where the choice falls between a tool that is available only in English, and another that is available in both languages, the latter should be preferred even if the functionality is slightly better in the former.

As you might imagine, this complication gave rise to different challenges than I dealt with even in my subsequent role in New York, where I was responsible for initiatives across the globe. Every demo we saw, every pilot we ran, was subject to the additional pressure - beyond the regular tests of technical excellence, requirements met, and intuitive UX - of French language functionality. During the course of my role at this firm, we provided in-depth feedback to many vendors on exactly how to tailor their tools for use with the French language.

But it was never easy. Nor was it always possible. Scaling machine learning algorithms for multiple languages, developing effective multilingual text classification for NLP, or even accommodating multiple jurisdictions of law within a database - all of these are labor- and time-intensive, and not necessarily worthwhile when the user base is limited (Quebec is a small market, especially in the context of all of North America).

Fast forward to 2019 (when this article was first written), during which I had the good fortune of traveling to a number of international events where I met people who share my passion for legaltech and who work in non-English language jurisdictions. People in Germany, Spain, Brazil, Lithuania, Finland, the Netherlands, France. I was fascinated to find that they are often severely limited in their capacity to utilize much of the legal technology on the market. Most legaltech does not yet allow for cross-jurisdictional, multilingual use.

Yes, international firms and companies will frequently adopt English as a universal language. But take, for example, a firm like COBALT. Headquartered in Lithuania, with a full Baltic presence, its lawyers regularly operate in four different languages - and they find it hard to widely adopt technology that doesn’t share this flexibility.

Or consider small to mid-sized firms and companies that operate squarely in one European or South American country. English-language-only tools fall short of meeting native lawyers’ (and clients’) needs.

Legaltech vendors, like vendors in any industry, gear their initial business to the markets where they can succeed fastest. Quick wins under the belt, money in the bag, means further development opportunities and scalability. It goes without saying that the most attractive markets are the biggest markets, markets where innovation is adopted most widely, and by firms with the deepest pockets. So it’s hardly surprising that the explosion of legaltech development - and investment therein - occurred first in the English-speaking world.

But after years of industry blogs and news sites touting “innovation” “AI” and “legaltech” as the sine qua non of any forward-thinking law firm, smaller markets want in. There has recently been an escalation in the number of legaltech start-ups emerging in Europe, South America, and beyond. These start-ups are not necessarily developing technology that is unreplicated elsewhere; rather, their point of difference lies in the operating language of the tools developed, or the jurisdictions thereby served. Consider the world of document automation. Beyond the big names we all know, there is Juriblox in the Netherlands, Avokaado in Estonia, Documendo in Denmark, Contraktor in Brazil, Legal Pilot in France, JianFabang (geared at start-ups) in China, and Wonder Legal, which originated in Spain and now serves multiple European, South American and Asian jurisdictions (and has launched into the U.S.). And that's just scratching the surface.

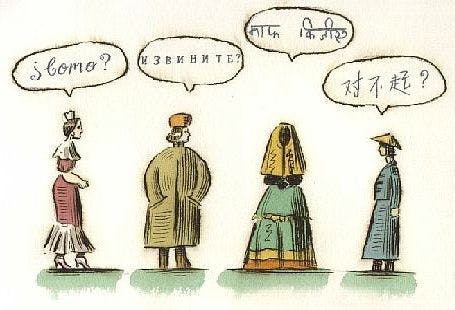

The result is a landscape populated by multiple tools that all do the same thing, but in different languages and with different jurisdictional applicability. The Tower of Babel, rebooted - separating us just as we have the opportunity to unite in our efforts to streamline the profession.

Much has been written recently about the need to consolidate legaltech vendors and tools. It would be remiss of us within those discussions to forget culture and language as another cause of problematic proliferation, and indeed another target for future clean-up.

Beyond capitalism and commercial pragmatism, are there other reasons why the available tools do not more broadly serve the international market? Not long ago I came across a series of articles online, highlighting the difficulties AI technology has with actually understanding language.

“There’s an obvious problem with applying deep learning to language,” writes Will Knight in MIT’s Technology Review. “It’s that words are arbitrary symbols, and as such they are fundamentally different from imagery. Two words can be similar in meaning while containing completely different letters, for instance; and the same word can mean various things in different contexts.”

If linguistic programming is difficult in even one language, imagine the complexity of building multi-lingual understanding into an AI system. Certainly this problem is an additional reason for the cultural divide in certain parts of the legaltech ecosystem. The resource-intensive nature of programming complex laws across multiple jurisdictions with different legal systems is no doubt another.

But what can we do about it? Is consolidation the answer? What can smaller or multilingual jurisdictions do in the meantime, so that they are not left behind in this race for innovation?

With the advent of generative AI and large language models such as OpenAI's ChatGPT, we may be closer to an answer than we were three years ago when I first wrote this article.

*This article (except for minor edits) was originally published on Tower of Babel - A Legaltech blog on July 31, 2019, and has been republished here with the author's permission.